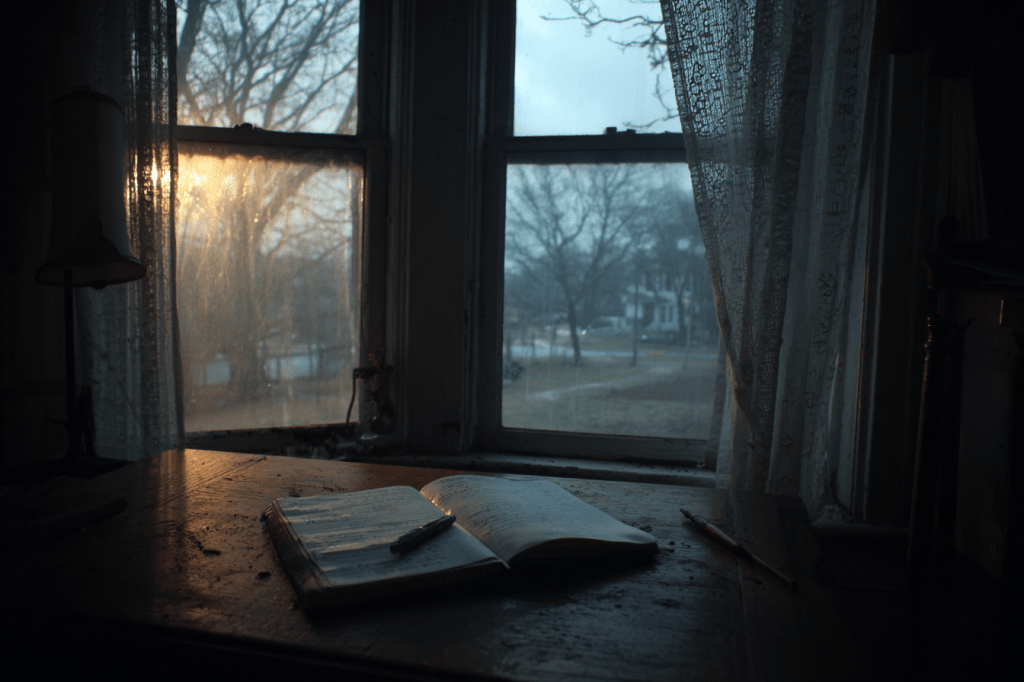

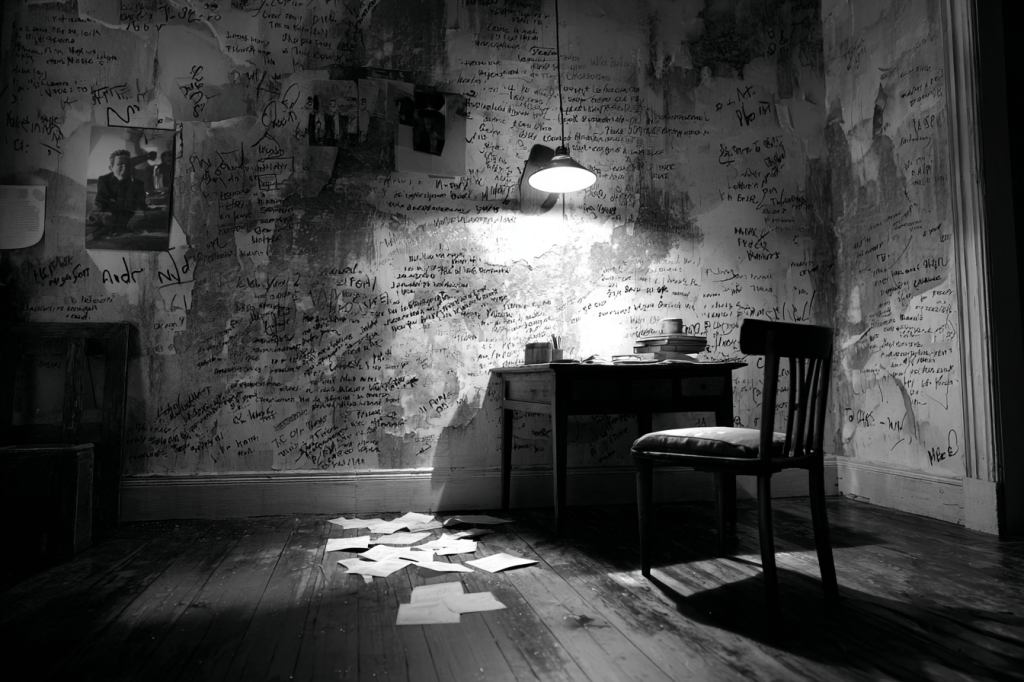

The ticking from the clock on the wall beat like a hammer against a concrete block—dust and debris flying, and every now and again a spark. That was my writing tonight. I had a head full of ideas but nothing with any heat. Then I heard something slide under the door. I froze for a second, thinking it might be the landlord bringing that “good news”—you know, thirty days and then it’s the bricks. But I remembered I’d caught that gig upstate with those high-class folks who wouldn’t know the blues if it hit them in the face, so I was good.

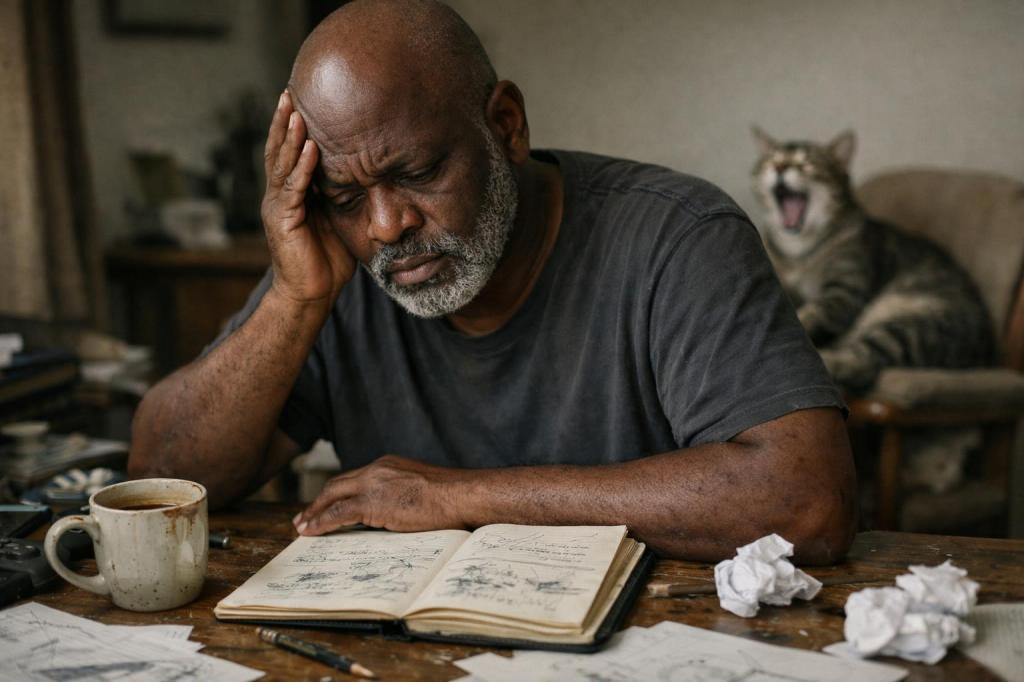

I walked to the door and looked down the hallway. Nothing. Then I saw Woodrow—the rat—gnawing on something. He paused long enough to size me up, then went back to work. I didn’t have the energy to do anything about it, and he knew it. Ms. Pearl, the neighbor’s tabby, slipped in through the gap and rubbed against my leg. I let her stay. Gave her some kibble, then hopped up on the edge of my desk. The page sat there, daring me to write something.

Someone once told me that’s how it starts: just sit in front of the typewriter and speak. Never worry about what you’re going to say; that part works itself out. Just don’t bitch out and you’ll be fine. Lamont Norman said that the day I bought his suitcase Royal typewriter. I laughed, thought he was kidding. He didn’t even smile. “I bitched out,” he said. “Good luck.” That was years ago. The typewriter’s still here—metal scarred, keys sticking like old grudges. I keep waiting for it to start talking first.

That’s when I noticed the envelope. Plain white. No stamp, no handwriting—just my name in black ink that bled a little, like the paper had been sweating. Inside: You are invited to The Draft. Midnight. The Double Down Tavern. That was it. No signature. No RSVP.

I laughed anyway. It sounded like something a drunk poet would dream up at closing time, but I stared at it longer than I should’ve. By eleven-thirty, I was tuning the Gibson, putting on the least-dirty shirt I owned, telling myself I wasn’t going. By midnight, I was already halfway there.

The Double Down? I’d heard of the place, but no one I knew had ever been there, and certainly nobody knew how to get there. It was one of those names that floated around in late-night stories—half joke, half rumor—always mentioned right before the bottle ran dry. I went down to the bodega on the corner for a pack of Luckies and to ask Mr. Park about it. Mr. Park knew everything worth knowing in this neighborhood: who owed rent, who got locked up, who was sleeping with whom.

But tonight he wasn’t there.

I can’t remember the last time I’d walked into that store and not seen him behind the counter, sitting on his stool, eyes glued to that little portable TV wrapped in enough tin foil to bake a potato. When the picture went fuzzy, he’d rap the side with his knuckles, nod, and mutter, “Everything just needs a good tap now and then.” The sound of that tap was part of the neighborhood’s heartbeat. Without it, the place felt wrong, too quiet, like the air had skipped a beat.

There was this strange woman behind the counter, somebody I’d never seen before, popping her gum slow. Who the hell pops gum slow? She didn’t even look at me when I asked for a pack of Luckies. Just slid them across the counter like she was bored of gravity. I decided to go for broke.

“Hey, you wouldn’t know how to get to the Double Down, by chance?”

She didn’t answer, just stepped out of sight for a second. When she came back, she slid a folded piece of paper across the counter. No words, no smile.

I opened it. It was an address. Nothing else.

I turned and walked out of the store, paper in one hand, cigarettes in the other. Halfway through the door, I looked back to thank her. She nodded without looking up, eyes still fixed on something only she could see. But in the glass of the door, I caught her reflection—and for half a heartbeat, I could swear her eyes were sparkling. Not with light. With recognition.

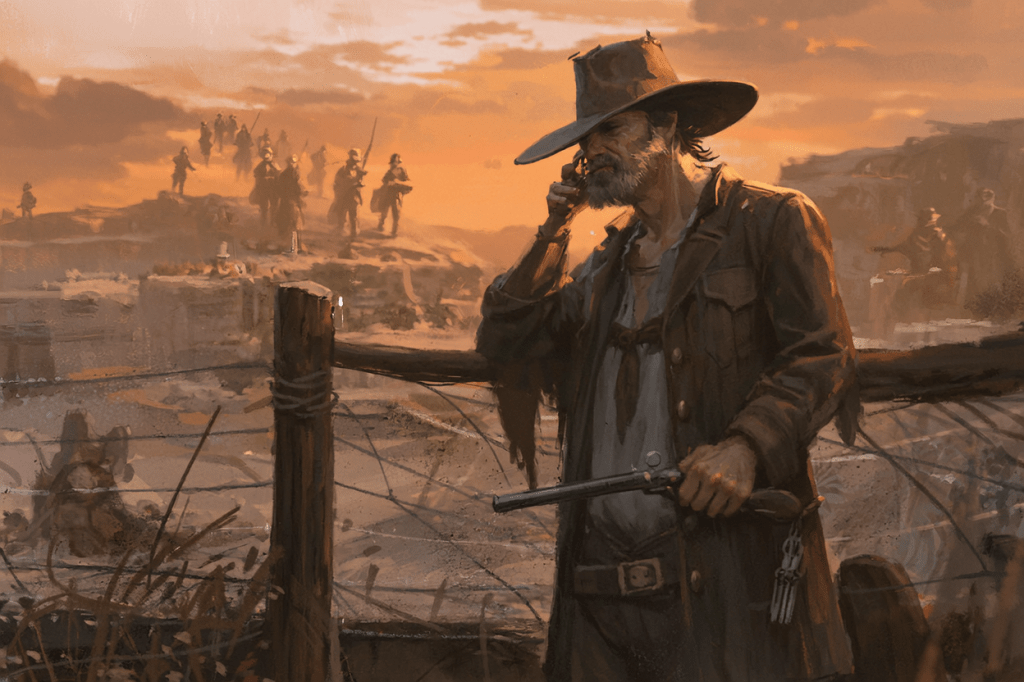

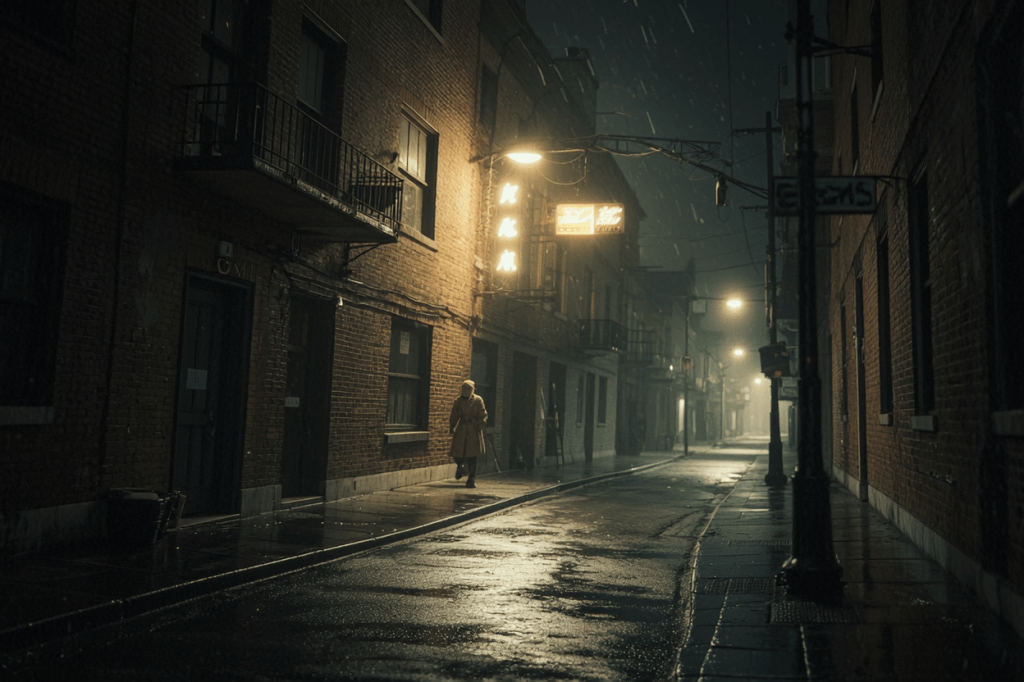

The address on the paper looked ordinary enough—just a number, a street I didn’t recognize. I lit a Lucky, watched the smoke coil off the end, and decided to walk. It wasn’t far, according to the city grid, but the grid had a habit of lying after midnight.

The streets were half empty, half asleep. A drunk kid laughed at a joke nobody told. A siren moaned somewhere uptown, fading slow like a horn section dying out. My shoes echoed too loud on the sidewalk; even the sound seemed to flinch.

I passed storefronts I swear I’d never seen before: a pawnshop that sold only typewriters, a record store where every sleeve in the window was blank white, a barber shop with a red neon sign that read OPEN but no reflection in the mirror.

The farther I went, the fewer streetlights there were. The city felt like it was backing away, leaving me to walk inside its ribs. I checked the paper again. The ink shimmered faintly, as if wet, and I realized I wasn’t reading a map—I was being led.

As I got close to the address, a drunk staggered out of the shadows and poked me in the chest. “Whatcha doin’?” he slurred, eyes glassy and mean. “You think you ready?”

I didn’t answer.

“You?” he barked again, then broke into laughter—loud, jagged, wrong. I pushed past him and kept walking, but when I looked back, the sidewalk was empty. The laughter stayed, close, right beside my ear.

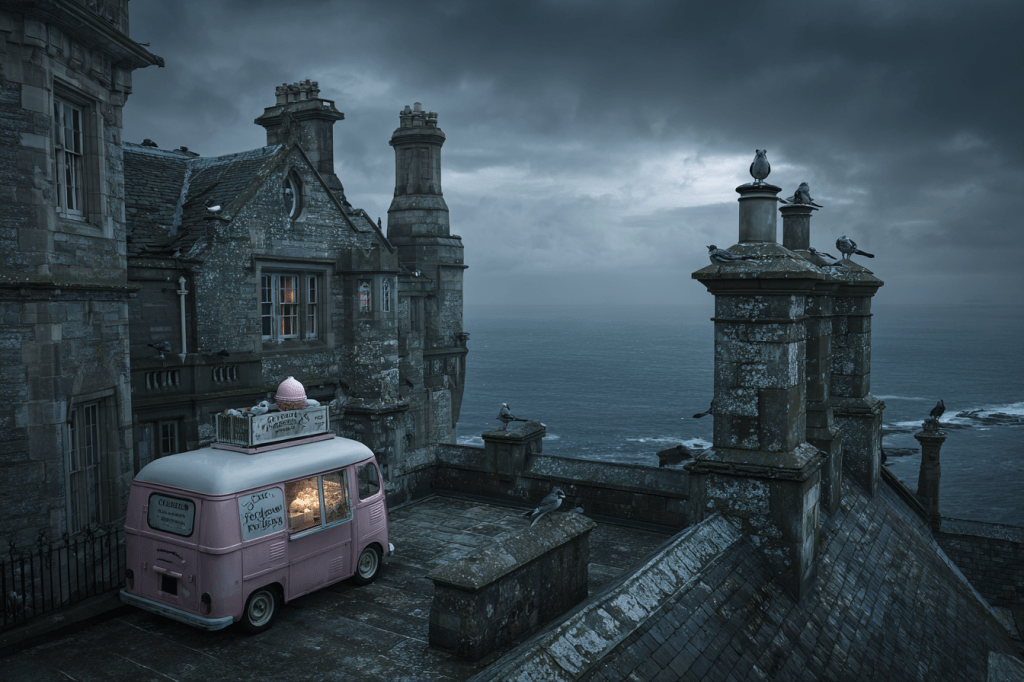

I stopped cold, heart hammering. Took another drag of my straight, exhaled slow. When the smoke cleared, I turned toward the street—and there it was, standing where the map said nothing should be.

The Double Down.

The door didn’t look like much—just wood and paint tired of each other—but the air around it hummed like a bass string. I could feel the groove before I heard it. Slow twelve-bar, heavy on the bottom end, something that could drag your sins across the floor till they begged for mercy.

I grabbed the handle. The damn thing was warm. When it opened, the sound hit me full in the chest—smoke, whiskey, perfume, electricity—all of it moving to the same beat. The door sighed shut behind me like it had been waiting to breathe again.

Inside, the room stretched wider than geometry allows. Corners bent. Shadows leaned the wrong way. Tables sweated rings from drinks poured before I was born. Every light was gold, every bottle looked like it had a soul trapped inside praying for one last round.

The crowd was a mix of then and now: drunks in denim, poets in funeral suits, a few specters in clothes older than jazz. One cat had a typewriter balanced on his knees, keys twitching on their own. Another wore a fedora that flickered in and out like a bad reception. Every time I looked straight at him, the air shimmered.

Behind the bar stood a woman with silver hair and a stare that could sand wood. She polished a glass that was already clean. The jukebox switched gears—Howlin’ Wolf growling through busted speakers—and the floorboards started to tap back.

I took a seat near the door, playing it cool. The bartender poured something the color of regret and set it in front of me.

“On the house,” she said, voice smooth as gin and twice as dangerous.

I looked around. At the back, a stage the size of a confession booth glowed red. A man sat there, guitar in his lap, fingers resting easy like he’d been born holding it. He didn’t play; he just watched me. Smile sharp enough to slice a chord.

“Place got a name?” I asked.

She half-smiled. “You tell me.”

The drink burned good going down—smoke and sugar and bad decisions. I blinked, and the room changed. Every face turned my way. No talking, no movement, just the weight of attention pressing down.

Then a man in a white suit stood by the jukebox and tapped his glass. The sound cracked the silence like a snare drum.

“Welcome,” he said, voice rolling through the room slow and mean. “Welcome to the Draft.”

The crowd answered with a low hum that crawled up my spine.

I could see there were a few guys like me who didn’t have a clue what the hell was going on. Then there were the ones who thought they did—scribblers with confidence and cologne, already imagining the book deals. I knew that breed. They never last. If it wasn’t so funny, it would’ve been tragic, but instead it was just pathetic.

The muses began to move—slow, gliding, half smoke, half skin. Each one shined in its own color. The room buzzed like a hive. They touched foreheads, whispered, and kissed some poor souls right on the mouth. Wherever they touched, something happened: laughter, sobbing, a glow under the skin.

Names were called. Not mine.

One by one, the seats around me emptied. The writers who’d been chosen vanished, or maybe just slipped sideways out of time. The unlucky ones sat frozen, pretending it didn’t matter, staring into their drinks like they could find meaning in the ice.

I kept my eyes down. The drink had gone warm.

A man near the jukebox started laughing too loudly. “Didn’t get the call, did ya?” he said to no one. “Guess you’ll be writing grocery lists now.” His laughter spread, nervous, contagious.

I waited. Nothing. No muse came my way.

The smug ones still sat upright, chins lifted, waiting to be crowned. I’d seen that look before at open mics and literary festivals—the face of somebody convinced the universe owed them a round of applause.

If it hadn’t been so funny, it would’ve been tragic. But right then, it just felt pathetic.

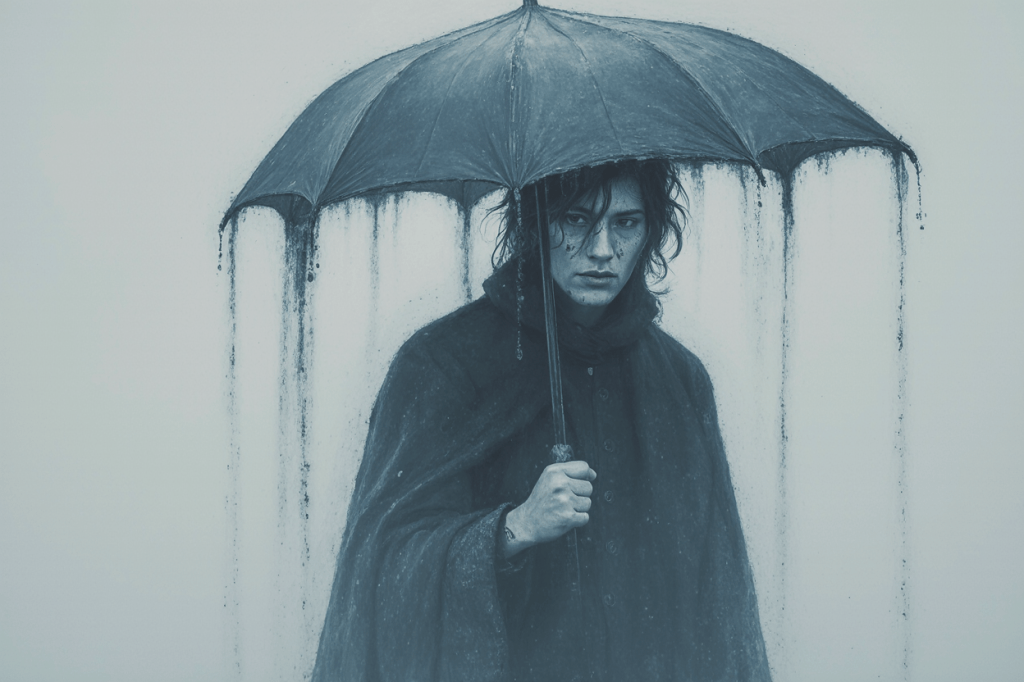

A thin, cold panic crawled up my spine. I was the last fool at the table. The muses had moved on. The man in white was clinking his glass again, ready to close the show.

I told myself I didn’t care. I told myself I’d been through worse. But I felt hollow—like a joke everyone else was in on.

I couldn’t believe this shit. I didn’t even know what The Draft was until an hour ago, and now it was already over. I didn’t get picked. Harry Lucas gets the nod? What the hell is going on?

To add insult to injury—Terry Best. Terry damn Best. Man hasn’t written a line worth reading since the Carter administration, and suddenly he’s chosen? Harry and I carried that sorry bastard for years. I’m jealous, sure. Harry’s good—better than I’ll ever admit out loud—but still, it stings.

“Congrats, you lucky fuck,” I muttered, raising my glass to no one. The drink burned all the way down, a reminder that some fires don’t keep you warm; they just scar you.

The room was thinning out. The chosen ones disappeared into the smoke with their shiny new partners. The rest sat there staring at the bar like it might offer consolation. Nobody spoke. The music died, the hum faded. For the first time all night, the silence had weight.

That’s when the folded piece of paper slid across the counter, slow and deliberate.

No one was near me. Nobody close enough to reach.

I hesitated, then picked it up. The paper smelled faintly of cigar smoke and cheap lipstick.

I unfolded it. Two words written in lipstick.

END