There are words we use carelessly, scattering them across people who haven’t earned them. Honor is not one of them. Honor is not a word; it’s a state of being. Many treat it as a relic from old books, a concept preserved in ink but forgotten in practice. We remember its definition, but not its discipline. Honor belongs to lives that can bear its weight—those whose choices reveal intent rather than performance, discipline rather than spectacle, substance rather than noise. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is one of the rare men whose life, lived deliberately and consistently, justifies the use of that word.

Long before trophies or records, before the skyhook carved its arc into basketball history, Kareem learned what it meant to walk a disciplined path. In Black Cop’s Kid, he writes about his father, a Black New York City police officer navigating a segregated America. His father moved through streets that demanded vigilance, wisdom, and restraint—a man required to inhabit two worlds that seldom acknowledged the full weight of his humanity. That quiet duality shaped Kareem’s earliest understanding of strength. His father did not preach lessons; he embodied them. The discipline in that household was not loud or performative. It was patient. Intentional. A way of carrying oneself when no one is watching. It was here that Kareem first learned that the inner life must be steadier than the world pressing against it.

As Kareem stepped into the national spotlight, that lesson met its first genuine test. His presence alone carried expectations that were not of his choosing. Every gesture, every silence, every interview became a canvas for projection. America demanded a familiar performance from its Black athletes—gratitude without question, humility without edge, excellence without voice. Kareem refused the performance. His reserve was mistaken for distance; his intellect, for defiance. Yet what much called aloofness was simply the discipline he had been raised with: the separation of worlds, protecting the private self, the refusal to let public hunger consume what must remain internal. Strength, for him, was never volume. It was alignment. And maintaining that alignment in the face of scrutiny became its own form of endurance.

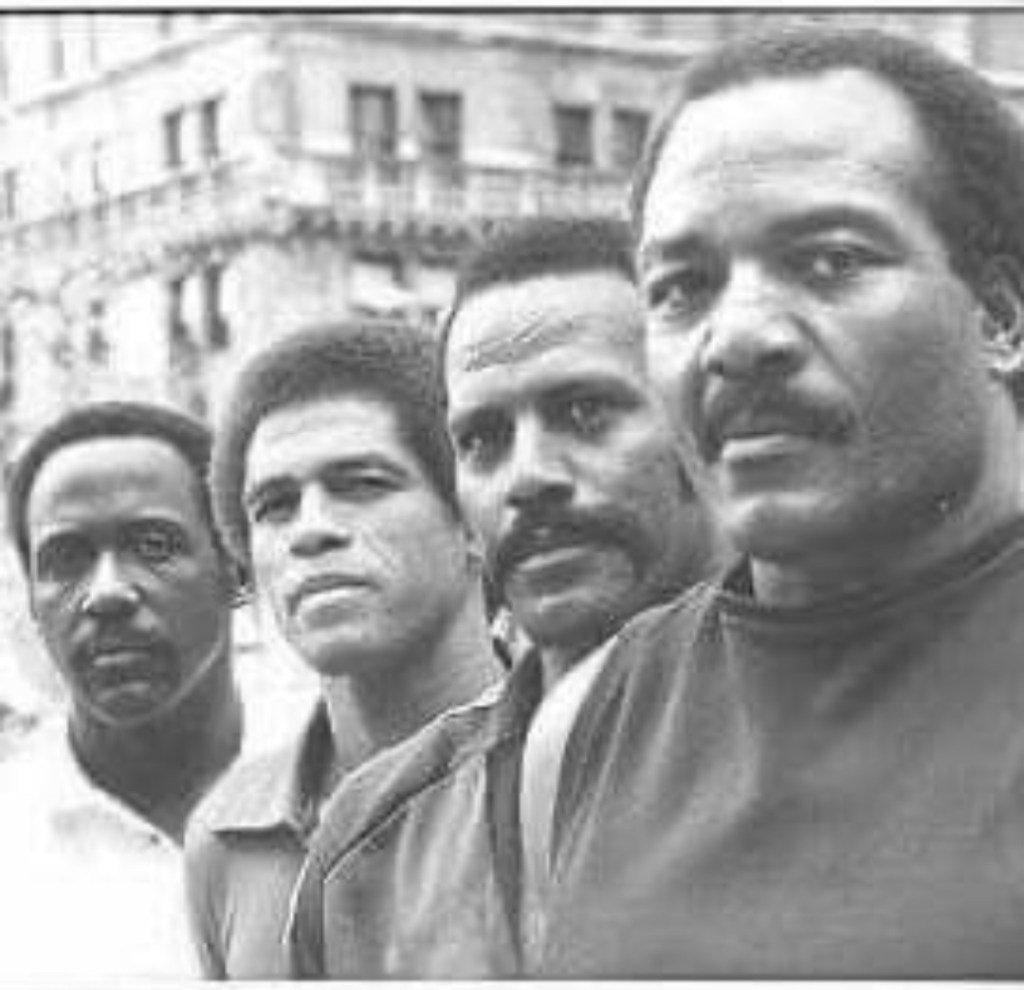

This alignment is what he carried into the moment that would sharpen his moral identity. In Black Cop’s Kid, Kareem describes being invited, at just twenty years old, to join a gathering now known as the Cleveland Summit. Jim Brown called him to sit alongside Bill Russell, Carl Stokes, Muhammad Ali, and other Black leaders—a room full of men who bore their own histories of struggle and conviction. They met to confront Ali’s refusal to be drafted into the Vietnam War. Some had served in uniform; others had walked the front lines of civil rights battles. The air in that room was a crucible, not a ceremony. Kareem entered as the youngest voice present, carrying the discipline of his father but stepping into a conversation that demanded clarity far beyond his years.

For hours, the group questioned Ali. They challenged his reasoning, his faith, his willingness to accept consequences. Ali argued that the war was being fought by people of color against people of color, for a nation that denied them basic civil rights. His refusal was rooted in religious conviction and moral clarity, not political theatrics. As Kareem recounts it, the debate grew heated—sharp questions, sharper answers, the weight of identity and duty pressing into every sentence. What emerged was not a portrait of a defiant champion but of a man prepared to sacrifice everything rather than betray his principles.

Bill Russell summarized what a good deal of felt but would not say aloud: he envied Ali’s “absolute and sincere faith.” Envy—not of fame or power, but of conviction. Kareem saw it plainly: even giants grappled with doubt. Even legends feared whether they could withstand the cost of conscience. In that moment, Kareem recognized a truth his father had lived without speaking—integrity is measured by what a person refuses to surrender. By the end of the Summit, they stood with Ali. Kareem left not with a slogan but with a direction. As he wrote, he felt he was finally doing something important rather than merely watching the world from its edges. His father’s quiet discipline had found its test, and it held.

That commitment of intent over performance would define the decades that followed. Kareem did not chase the spotlight. He did not soften his seriousness to become more palatable. His writing, activism, and public presence reflect a consistent refusal to be shaped by expectation. In a culture that rewards noise, he chose depth. In an era that prized spectacle, he chose substance. His reserve was not distance—it was stewardship of the inner life his father taught him to protect.

This same ethos threads through his work beyond basketball. In Brothers in Arms, his tribute to the 761st Tank Battalion of Black soldiers in World War II, he writes of men whose greatest acts were known only in fragments. Many lived entire lives without revealing what they had endured. Their silence was not secrecy—it was dignity. Kareem writes about them with reverence, humility, and a recognition that some forms of service cannot be measured by praise. In many ways, his own life echoes theirs: principled choices, quiet strength, a preference for action over advertisement. Deeds, not words, as the old motto says.

Across time, the pattern of his life remains coherent. The public, private, and secret selves that his father taught him to guard align under a single discipline: to move with intent, even when misunderstood. The same steadiness that kept his father upright on hostile streets steadied Kareem through shifting eras, hostile headlines, and the long shadow of fame. His reserve is no longer misread when viewed through this lens. It becomes what it always was: a disciplined way of walking through a world eager to consume more than it has earned.

Most athletes earn admiration. Very few earn Honor. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar does, not because he was flawless or universally embraced, but because he lived with deliberate intent when it would have been easier to drift, and with discipline when it would have been easier to perform. Honor is not a word; it is a state of being. And if we are to use that word with any seriousness, we should reserve it for lives capable of carrying its weight. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s life is one of them.