Song Lyric Sunday • Theme: Rivers, Streams, Creeks, Brooks

We got those Sunday Jazz Vibes going. It’s never intentional, but it’s always right. The slow grooves of Grover Washington Jr. set the tone before the coffee even cools. The things that man does with a sax ought to be illegal in a few states.

“East River Drive” rolls in like a slow-moving tide — smooth on the surface, dangerous underneath. It’s one of those tracks that pretends to be background sound until you realize you’ve stopped whatever you were doing just to follow the way he bends a note. That sly confidence, that river-road swagger. The rhythm section lays back like it’s got nowhere to be, while Grover glides above it all, mapping the emotional coastline of a Sunday morning.

A subtle deep groove — the kind that whispers instead of shouts, trusting you’ll lean in.

And somewhere between those warm horn lines and the long exhale of morning, my mind drifted downstream. That’s when the tonal shift hit — jarring in the best possible way.

Sliding from Grover into Melody Gardot is like stepping out of warm light into cool river air. Grover softens the room; Gardot sharpens it. His sax gives you glide. Her voice gives you gravity. With Grover, the river moves. With Gardot, the river speaks.

She pulls you in with that first line:

“Love me like a river does.”

On paper, it’s simple.

In her mouth, it’s a philosophy.

The river isn’t passion.

It’s not urgency.

It’s not the cinematic love-story nonsense we were raised on.

A river flows.

A river returns.

A river shapes the land without ever raising its voice.

She’s not asking for fireworks.

She’s asking for endurance.

Then the quiet boundary:

“Baby don’t rush, you’re no waterfall.”

That’s the deal-breaker disguised as tenderness.

The waterfall is the crash, the spectacle, the “falling in love” that feels good until you’re pulling yourself out of the wreckage.

She wants none of that.

Her voice is soft, but the boundaries are steel.

Strip away the romance of rivers and waterfalls and what she’s really saying is:

“If you’re going to love me, do it in a way that won’t break me.”

That’s not fear.

That’s experience.

The next verse shifts from river to sea — steady flow to swirling depth. Not for drama. For honesty. Intimacy always disorients you a little.

But even in that turbulence, she returns to her anchor: no rushing, no crashing, no spectacle. Even the sea has tides. Even passion needs rhythm.

Then the lens widens — earth, sky, rotation, gravity. Love as cycle, not event. Love that keeps you grounded without pinning you down.

And then back to the whisper:

“Love me, that is all.”

Simple words.

Colossal meaning.

What I love about this track is that it refuses to lie.

It doesn’t speak of love the way movies do — all gush, sparks, and declarations nobody could sustain after the credits roll. Gardot isn’t chasing fireworks. She’s not interested in romance that burns hot and disappears just as fast.

She’s talking about grown-folk love.

The kind that shows up.

The kind that lasts.

The kind built on years, not moments.

Her metaphors — river, sea, earth — aren’t poetic decoration. They’re durability tests:

Can your love flow?

Can it deepen?

Can it cycle?

Can it stay?

She’s asking for a love that tends a lifetime, not a scene. A love shaped by presence, not passion; by commitment, not chaos.

The kind you don’t stumble into.

The kind you earn.

And maybe that’s why this one gets me every time — there’s a difference between love that excites you and love that holds you. I’ve lived long enough to know which one matters more.

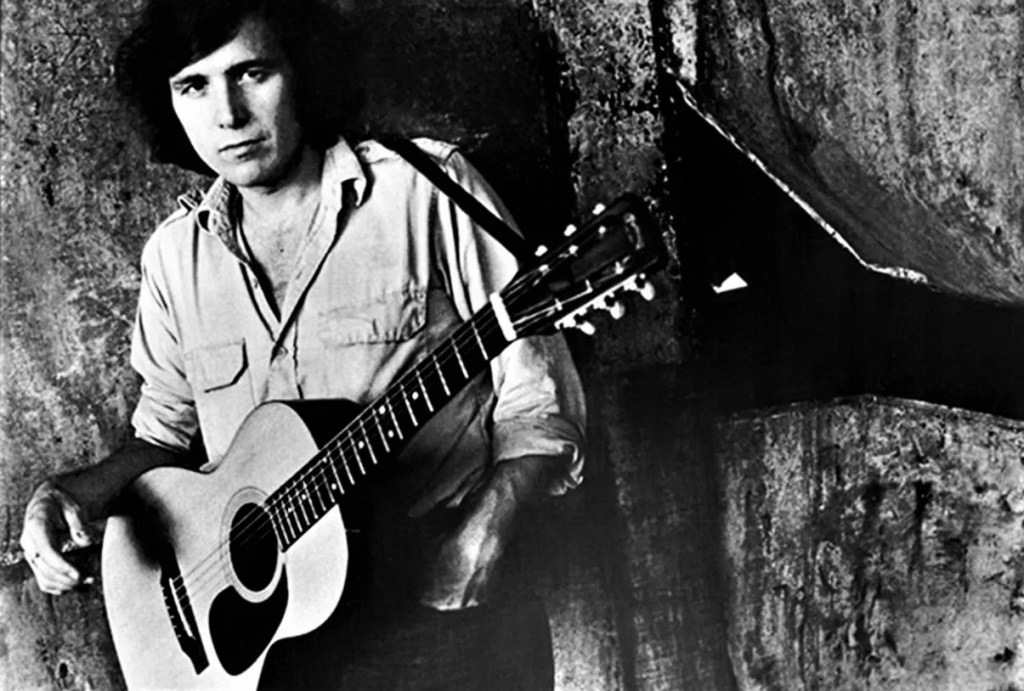

And let me say this plainly: this track comes from Melody Gardot’s debut album. Worrisome Heart was her first offering to the world, and I’ve rarely seen that kind of sophistication and grace appear so fully formed on a debut. Most artists spend years trying to grow into this kind of emotional control — the restraint, the nuance, the quiet authority. Gardot walked in with it from day one. No hesitation. No warm-up laps. Just a young artist already carrying the poise of someone who’s lived a lifetime and managed to distill it into song. Truly a marvel.

Before you watch the performance below, a quick note:

This reflection is based on the studio version of “Love Me Like a River Does,” from Worrisome Heart — the quiet, intimate rendition where she whispers the philosophy of grown-folk love straight into your chest. But in the live version you’re about to hear, she opens with something unexpected: the first verse of Nina Simone’s “Don’t Explain.” It’s a deliberate nod — smoky, weary, full of Simone’s emotional steel — and Gardot weaves it in so seamlessly you barely notice the transition until it’s done. One moment you’re in Nina’s world of bruised truth; the next, Gardot slips into her own song like it was always meant to follow. It turns the piece from a gentle plea into something closer to a declaration.

What makes the song hit is how Gardot never pushes. The arrangement stays minimal. The room stays dim. Every breath has space around it.

It’s intimacy without intrusion.

Truth without theater.

A quiet manifesto from someone who knows the cost of loving too fast and too violently.

She’s asking for love like water — not the kind that drowns you, but the kind that carries you and keeps coming back.

A grown-folk kind of love.

A river kind of love.

The kind that lasts because two people choose the flow over the fall.

And maybe that’s the real Sunday lesson — some songs don’t need volume to be heard. Some just need stillness.