CHALLENGE RESPONSE – SONG LYRIC SUNDAY

Here is my response to Jim Adams’ Song Lyric Sunday

As a child, I can hardly remember when I listened to the radio and didn’t hear this song at least once. I heard so much I memorized the lyrics and sang right along. Yet, as time went on, I found myself growing tired of hearing this song. I remember wondering what was going to be the next big hit? I didn’t realize the song was already several years old. It’s such a timeless classic I had to take a moment and discuss its meaning. This is what I came up with.

The Layers of Meaning in “American Pie”

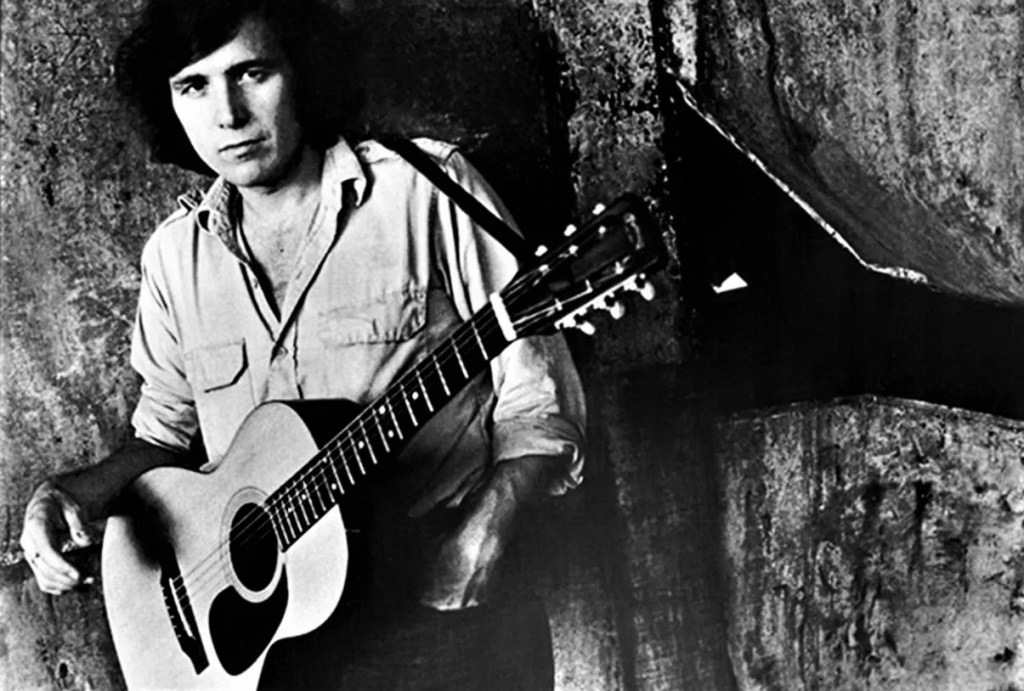

Don McLean’s iconic song “American Pie” has captivated audiences for decades with its enigmatic lyrics and haunting melodies. Released in 1971, the eight-and-a-half-minute epic is steeped in cultural references, historical events, and personal reflections, inviting listeners on a journey through the turbulent landscape of American society in the 20th century. As one of the most analyzed and debated songs in popular music history, “American Pie” continues to fascinate and inspire, offering layers of meaning that transcend time and space.

At its core, “American Pie” is a lamentation for the loss of innocence and idealism in American society and a nostalgic homage to the golden era of rock and roll. The song opens with the poignant line, “A long, long time ago, I can still remember how that music used to make me smile,” evoking a longing for the simpler times of youth and the transformative power of music to unite and uplift.

Central to the song’s narrative is the tragic plane crash that claimed the lives of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and The Big Bopper on February 3, 1959, often referred to as “The Day the Music Died.” This event serves as a metaphor for the loss of innocence and optimism in American society, marking the end of an era of rock and roll idealism and the onset of a more turbulent and uncertain period in history.

McLean weaves a tapestry of cultural references and symbolic imagery throughout the song, drawing on Americana, mythology, and spirituality themes to create a rich and evocative narrative. The lyrics are peppered with allusions to historical figures, events, and symbols, from “the King” (Elvis Presley) to “the jester” (Bob Dylan), from “the sacred store” (the record store) to “the holy dove” (a symbol of peace and spirituality).

One of the most debated aspects of “American Pie” is the interpretation of its cryptic lyrics, which have spawned countless theories and analyses over the years. Some interpretations suggest that the song is a commentary on the decline of American society and the loss of traditional values. In contrast, others see it as reflecting popular culture’s changing landscape and commercialism’s rise.

Yet, amidst the ambiguity and complexity of its lyrics, “American Pie” ultimately serves as a testament to the enduring power of music to transcend boundaries, unite disparate voices, and capture the collective consciousness of a generation. As McLean once said, “American Pie” is “a big song with big themes,” encompassing an entire nation’s hopes, dreams, and aspirations.

In conclusion, “American Pie” is a timeless masterpiece that defies easy categorization and interpretation. Its evocative imagery, poetic lyricism, and haunting melodies resonate with listeners of all ages, inviting them to ponder the mysteries of life, love, and loss. Whether viewed as a nostalgic tribute to the golden age of rock and roll or a poignant lament for the loss of innocence in American society, “American Pie” remains a symbol of hope, resilience, and the enduring power of music to inspire and uplift.

American Pie Lyrics

A long, long time ago

I can still remember how that music

Used to make me smile

And I knew if I had my chance

That I could make those people dance

And maybe they’d be happy for a while

But February made me shiver

With every paper I’d deliver

Bad news on the doorstep

I couldn’t take one more step

I can’t remember if I cried

When I read about his widowed bride

Something touched me deep inside

The day the music died

So, bye-bye, Miss American Pie

Drove my Chevy to the levee, but the levee was dry

And them good ol’ boys were drinkin’ whiskey and rye

Singin’, “This’ll be the day that I die

This’ll be the day that I die”

Did you write the book of love

And do you have faith in God above

If the Bible tells you so?

Now, do you believe in rock ‘n’ roll

Can music save your mortal soul

And can you teach me how to dance real slow?

Well, I know that you’re in love with him

‘Cause I saw you dancin’ in the gym

You both kicked off your shoes

Man, I dig those rhythm and blues

I was a lonely teenage bronckin’ buck

With a pink carnation and a pickup truck

But I knew I was out of luck

The day the music died

I started singin’, bye-bye, Miss American Pie

Drove my Chevy to the levee, but the levee was dry

Them good ol’ boys were drinkin’ whiskey and rye

Singin’, “This’ll be the day that I die

This’ll be the day that I die”

Now, for ten years we’ve been on our own

And moss grows fat on a rollin’ stone

But that’s not how it used to be

When the jester sang for the king and queen

In a coat he borrowed from James Dean

And a voice that came from you and me

Oh, and while the king was looking down

The jester stole his thorny crown

The courtroom was adjourned

No verdict was returned

And while Lenin read a book on Marx

A quartet practiced in the park

And we sang dirges in the dark

The day the music died

We were singin’, bye-bye, Miss American Pie

Drove my Chevy to the levee, but the levee was dry

Them good ol’ boys were drinkin’ whiskey and rye

Singin’, “This’ll be the day that I die

This’ll be the day that I die”

Helter skelter in a summer swelter

The birds flew off with a fallout shelter

Eight miles high and falling fast

It landed foul on the grass

The players tried for a forward pass

With the jester on the sidelines in a cast

Now, the halftime air was sweet perfume

While sergeants played a marching tune

We all got up to dance

Oh, but we never got the chance

‘Cause the players tried to take the field

The marching band refused to yield

Do you recall what was revealed

The day the music died?

We started singin’, bye-bye, Miss American Pie

Drove my Chevy to the levee, but the levee was dry

Them good ol’ boys were drinkin’ whiskey and rye

Singin’, “This’ll be the day that I die

This’ll be the day that I die”

Oh, and there we were all in one place

A generation lost in space

With no time left to start again

So, come on, Jack be nimble, Jack be quick

Jack Flash sat on a candlestick

‘Cause fire is the Devil’s only friend

Oh, and as I watched him on the stage

My hands were clenched in fists of rage

No angel born in Hell

Could break that Satan spell

And as the flames climbed high into the night

To light the sacrificial rite

I saw Satan laughing with delight

The day the music died

He was singin’, bye-bye, Miss American Pie

Drove my Chevy to the levee, but the levee was dry

Them good ol’ boys were drinkin’ whiskey and rye

Singin’, “This’ll be the day that I die

This’ll be the day that I die”

I met a girl who sang the blues

And I asked her for some happy news

But she just smiled and turned away

I went down to the sacred store

Where I’d heard the music years before

But the man there said the music wouldn’t play

And in the streets the children screamed

The lovers cried, and the poets dreamed

But not a word was spoken

The church bells all were broken

And the three men I admire most

The Father, Son and the Holy Ghost

They caught the last train for the coast

The day the music died

And they were singin’, bye-bye, Miss American Pie

Drove my Chevy to the levee, but the levee was dry

And them good ol’ boys were drinkin’ whiskey and rye

Singin’, “This’ll be the day that I die

This’ll be the day that I die”

They were singin’, bye-bye, Miss American Pie

Drove my Chevy to the levee, but the levee was dry

Them good ol’ boys were drinkin’ whiskey and rye

Singin’, “This’ll be the day that I die”