TUNAGE – THROWBACK THURSDAY

A jazz legend. A folk icon. One final act of creative defiance.

When Joni Mitchell dropped Mingus in 1979, it threw everyone for a loop. Critics scratched their heads; fans wondered where the dulcimer had gone. It didn’t sound like Blue, or Court and Spark, or anything even remotely close to her folk-pop reputation. And honestly? Joni didn’t care.

“This wasn’t just a genre crossover — it was a genre collision.”

This was Charles Mingus’s final project. ALS had stolen his ability to play, but not his impulse to push boundaries. So instead of retreating into legend, he reached out to Joni Mitchell — the queen of tunings, lyrics, and curveballs — and asked her to set words to some of his compositions. She said yes.

The result was a challenging listen — five spoken-word “raps,” interludes pulled from their conversations, woven between rich, angular jazz compositions. It was intimate, raw, and not made for background listening. You don’t just hear music — you hear mortality, mischief, and Mingus grumbling like a jazz prophet in a wheelchair.

“Mingus couldn’t play anymore, but he wasn’t done.”

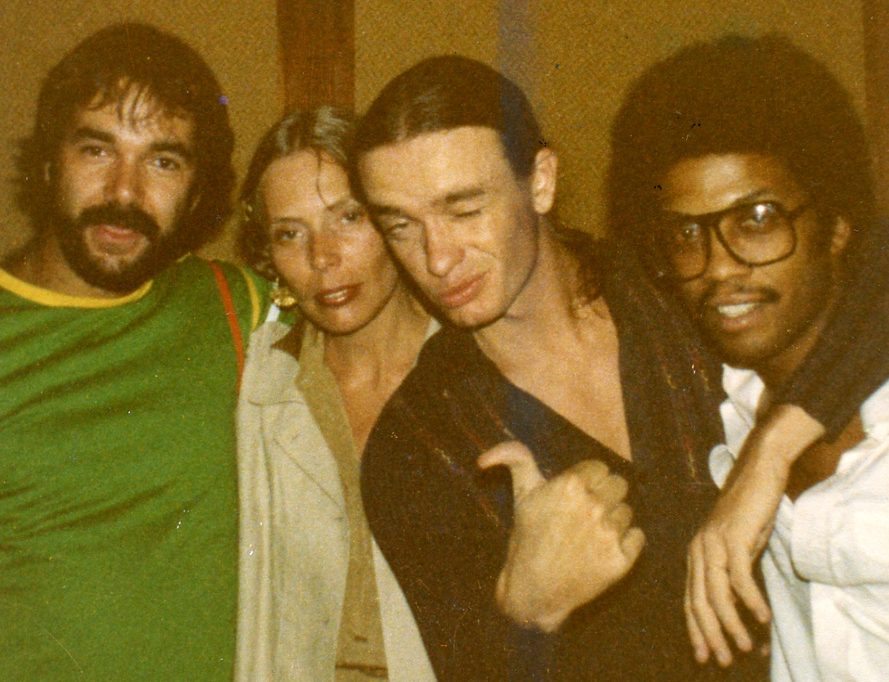

Mitchell described their first meeting like this:

“The first time I saw his face it shone up at me with a joyous mischief… Charlie came by and pushed me in—‘sink or swim’—him laughing at me dog paddling around in the currents of black classical music.”

Translation: Mingus didn’t want a tribute. He wanted a partner with nerve.

The lineup was no joke:

- Jaco Pastorius on bass (melting frets like butter)

- Wayne Shorter on sax (bending the air around him)

- Herbie Hancock on electric piano (tickling the keys like he invented them)

- Peter Erskine and Don Alias holding down rhythm

- Plus wolves — yes, wolves — on “The Wolf That Lives in Lindsey”

“She didn’t smooth the edges — she leaned into the mess.”

This isn’t dinner-party jazz. It’s messy, meandering, occasionally maddening. But it has guts. At one point, Mingus told her she was singing the wrong note.

She replied, “That note’s been square so long it’s hip again.”

Mingus, without missing a beat: “Put in your note, my note, and two grace notes too.”

That’s the whole album right there — layered, irreverent, and unbothered by convention.

From Skeptic to Fan

My journey into Joni Mitchell’s world didn’t start with a musical epiphany. It started with a woman — one who casually mentioned that Prince was a fan of Joni Mitchell. I made a face. Possibly several. My inner monologue said: Oh great, another misunderstood-genius folk artist I’m supposed to pretend to like.

But then I saw her vinyl collection.

Not a greatest-hits graveyard. Not recycled top 40 safe bets. Her shelves were full of weird, daring, intentional records — the kind people own because they listen, not just display. I started paying attention.

I got home, looked up Joni’s discography, and there it was: Mingus. Charles Mingus? With her? I hit play.

Then I heard him — the voice. The Maestro. Laughing, breathing, alive. For a second, I thought I’d stumbled onto a secret Mingus record.

Then the bass came in. And I paused.

This isn’t Mingus on bass. But the lines were liquid, wild.

Then the piano hit. I stopped. “Who’s tickling the keys like that?” I muttered. I knew that sound. Herbie Hancock.

This was no crossover fluff. This was a full-on creative risk with real players and real weight.

I stopped the record, called her, and said:

“Okay — what’s the Joni Mitchell starter kit?”

She gave it to me. Blue. Hejira. Court and Spark.

I listened. And suddenly, the whole picture came into focus.

I came back to Mingus later — and this time, I didn’t feel lost. I was ready. I didn’t need it to make sense immediately. I just needed to meet it where it was.

Critical Reception: Then and Now

Upon its release in 1979, Mingus got a lukewarm reception.

Stereo Review said it had “no improvisation.” Robert Christgau gave it a C+, calling it a “brave experiment” that didn’t quite succeed.

Folk fans missed the softness. Jazz critics missed Mingus’s hands. Everyone expected something different — and Mingus gave them none of it.

But over time, things changed. Today, Mingus is respected for what it is: bold, strange, and ahead of its time.

“After four decades, the deeply personal and experimental Mingus has grown into one of the most important titles in the Mitchell catalog.”

— Ron Hart, GRAMMY.com

Even those who played on it are reflecting differently now:

“It was and remains a brave project and statement… an essential piece of not only Joni’s library of music, but of American music in the late 1970s.”

— Peter Erskine, drummer on Mingus

Funny how time — and maybe a little patience — can change everything.

Final Word

Mingus isn’t cozy. It’s not an easy listen. It’s not even especially likable at first.

But it’s real.

Two artists — one dying, one evolving — making something on their own terms. No pandering. No hand-holding. Just music, conversation, and courage.

I started listening to Joni Mitchell because of a woman.

But I kept listening because Mingus didn’t try to win me over.

It made me meet it halfway.

And once I did, I never looked at music — or Mitchell — the same way again.

Love this one too, Mangus. My exposure comes from the Charles Mingus end of things. He’s one of my favorite bass players and composers. I love Epitaph, his long work that was composed as a tribute to Eric Dolphy. Especially the song “Freedom.” Eventually I got the concert version of Shadows and Light, Joni Mitchell’s live show partially based around this album. The real revelation on the DVD is Jaco Pastorius. His performance of Slang is so cool. Now that was a bass player. Joni’s search for something deeper really paid off.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When, I discovered Jaco, I must have listened to him for at least a month. I’m huge Mingus as well. I knew nothing about Mitchell. I haven’t heard Epitaph yet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good write-up on an album I haven’t yet heard. Now, of course, I must listen to it and get back with you on it. Happy Friday!

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you, Lisa

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome.

LikeLike

Just finished listening to it via YouTube (via DuckDuckGo’s Duck Player, with no ads) and am very surprised at how much the music reminds me of Chick Corea’s album, “Return to Forever,” released in Sept 1972. Then I wiki-ed Mingus’ career and see his discography starts in 1953. Hearing Joni singing along to the jazz tunes threw me a little but my listening ear adjusted. I like those little couple-of-second breaks. The first one, where Joni contradicts Mingus on his age (WTH!? A person knows their own age!) It will take a few more listens to see if/when favorites emerge. Like Return to Forever, Mingus was a very enjoyable listen. A really good collaboration between two very strong musical creatives.

LikeLiked by 2 people

When I first read this I thought you were talking about the supergroup called Return to Forever which included Chick Corea. Then I looked up the album you mentioned and was surprised when the Corea album. It’s only 4 tracks so I should be able to listen to it this weekend. Thanks for recommendation.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think the name of the band and the album are the same? They (band and album) are winners in my book.

LikeLike