TUNAGE – THROWBACK THURSDAY

Author’s Note: This article was originally written for Jim Adams’ Song Lyric Sunday, but I forgot to post it… oops.

Greatest hits albums fed us what we already knew. Mixtapes fed us what we didn’t even know we needed. This wasn’t about hits; it was about heart. About craft. About rebellion. In a world that settled for convenience, we chose meaning. And we built it, one song at a time.

There was a time when a “greatest hits” album promised the world and delivered little more than a shallow sampler. You walked into a record store, hopeful, only to find a shiny package filled with chart-chasing fluff, predictable tracklists, and maybe — if you were lucky — one or two songs you actually cared about.

For real music lovers, the greatest hits album was a betrayal. So we made something better: the mixtape.

The Mixtape: A Sacred Artform

Before playlists, before algorithms, there was the mixtape. But a mixtape wasn’t just a collection of songs. It was a statement. A curated, sequenced, and deeply personal offering.

Creating a mixtape meant something. It wasn’t about speed or convenience. It was about intention — about crafting a narrative that unfolded song by song. Each track was a chapter. Each transition is a carefully measured pause, a breath in the story.

You thought about the mood, the flow, and the emotional weight of every decision. Every track had a purpose. Every transition was considered. You didn’t just hit record — you crafted an experience.

You wrote out the tracklist by hand, agonized over timing, and re-recorded entire sides if a song didn’t fit. The case was decorated with doodles, magazine cutouts, scraps of personal history. In a way, you weren’t just sharing music; you were sharing yourself.

Mixtapes were acts of vulnerability. They were slow art in a fast world.

Why Greatest Hits Albums Let Us Down

Most greatest hits albums were designed by marketing departments, not musicians. They weren’t about storytelling — they were about sales.

- They skipped deep cuts that real fans lived for.

- They threw in new songs no one asked for.

- They sequenced tracks by chart position, not emotional resonance.

Greatest hits albums too often strip music of its context — they offer songs without the journey, choruses without the verses. They were snapshots when what we craved was a full-length film.

And then there was K-Tel — the kings of the cash-in compilation. K-Tel would slap together a dozen radio edits, chop down songs for time, and cram them onto a single vinyl. These weren’t albums — they were sonic fast food. No vibe, no flow, no soul.

We wanted more. We wanted music to mean something. So we made it ourselves.

The Record Store: Temple of Taste

Finding the right record store was part of the rite of passage. You didn’t go to the mall. That was for tourists.

You found the secret spot — basement-level, behind a laundromat, no signage, just a door covered in band stickers. Inside: crates of vinyl, walls of obscure posters, and the Jedi behind the counter.

The staff weren’t clerks; they were gatekeepers. They didn’t just sell music; they shaped your journey through it. They tested you, judged your picks, and only shared their real knowledge if you proved you were serious.

Every trip was a lesson in humility and discovery. You learned to dig, to research, to listen with intention. You learned that taste wasn’t about what you liked — it was about what you understood.

In these sanctuaries of sound, music wasn’t just background noise — it was the lifeblood of identity.

Mixtapes Were a Rebellion

Mixtapes fixed what greatest hits albums broke.

- They had a theme.

- They had emotional sequencing.

- They combined hits and deep cuts with purpose.

Mixtapes were the purest form of musical self-expression. They weren’t made for everyone — they were made for someone. For a friend, a lover, a crush, or maybe just for yourself.

They were personalized, handmade, and built for a specific mood or moment. Mixtapes were proof you knew music, not just what was fed to you.

In a way, they were quiet acts of defiance against mass production. They said: I’m not here for the hit parade. I’m here for something real.

When Greatest Hits Got It Right

Despite the letdowns, a few greatest hits albums actually nailed it.

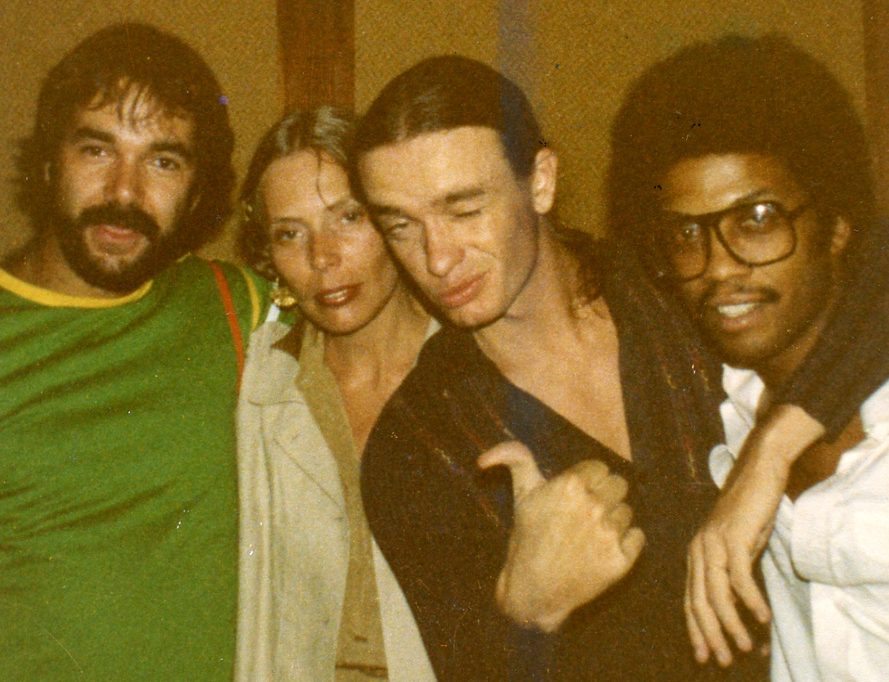

For me, it started with The Best of Earth, Wind & Fire, Vol. 1.

Golden cover, timeless tracks, perfect flow. From “Got to Get You Into My Life” — a Beatles cover reimagined into pure, brassy soul-funk — to “September” and “Shining Star,” it didn’t feel like a compromise. It felt like a celebration.

Earth, Wind & Fire didn’t just repackage — they redefined. They reminded us that a greatest hits album could tell a story if you cared enough to sequence it like one.

And they introduced me to the quiet genius of Al McKay, the guitarist whose rhythm work underpinned so many of their classics. McKay wasn’t flashy. He wasn’t a solo king. But his grooves on “September,” “Shining Star,” and “Reasons” built the very foundation that generations danced to.

Without him, an entire era might have been grooveless.

Other albums got it right too: Queen – Greatest Hits (1981), Bob Marley & The Wailers – Legend (1984), ABBA – Gold (1992). These weren’t just collections; they were time capsules of feeling.

The Spirit Lives On

Today, we have playlists. We have algorithms. But the spirit of the mixtape still lives: in crate-diggers hunting for vinyl, in DJs building a night’s setlist with intention, in anyone who believes that how you present music matters as much as what you play.

Music, at its best, is not about accumulation. It’s about connection.

The mixtape wasn’t just a reaction to bad greatest hits albums. It was a revolution. A rebellion against mediocrity. A quiet, persistent demand for meaning.

And we’re still feeling it.

“Anyone can collect songs. It takes a real heart to make them matter.”