Air of December by Edie Brickell and the New Bohemians

December is a month of conflicting mindsets. On one hand, people get swept up in the season and start doing “Good Things,” as if generosity is something they dust off once a year like ornaments from the attic. Smiles get bigger. Voices get lighter. Folks try to be kinder, cleaner versions of themselves — at least for a few weeks.

But not everyone rises with the cheer.

Some slip the other way — into that deep, cold room December knows how to unlock. The early darkness settles on their shoulders. The empty chairs at the table get louder. They watch the world light up and feel nothing but the distance.

The weather has changed. We felt the shift back in November — a quiet warning — but December carries the truth in its bones. The calendar hints at winter, but nature tells you outright. Woodchucks waddle with purpose, grabbing whatever scraps they need to seal themselves away. Raccoons run their winter reconnaissance, scouting warm corners with criminal determination.

Across the street, after sundown, the trees start speaking. Leaves rustle in patterns the wind doesn’t claim. Then: silence. Then another rustle — heavier this time — followed by a shadow shifting where it shouldn’t. And there it is:

a raccoon the size of a small planet climbing like gravity signed a waiver. Somehow that bandit-faced acrobat is perched on the roof of a three-story house, staring down like it owns the deed.

Meanwhile, Christmas trees bloom behind neighborhood windows — soft glows behind glass, promises of borrowed joy. For the next thirty days, people will act like saints in training, as if kindness has a seasonal password and only December knows it. Christmas carols creep through grocery aisles. Decorations multiply like mushrooms.

This is precisely why you need a strong music collection.

Survival gear.

Armor.

Because there are only so many versions of “Jingle Bells,” “White Christmas,” “Deck the Halls,” and “Frosty the Snowman” a person can take before something in them snaps.

Though Frosty and Rudolph do have their… alternative interpretations — the ones no one plays around polite company. Those versions? Those have some soul to them.

The lights are up on half the streets by now — fake pine needles, borrowed glow, holiday cheer on rotation. But behind windows, in alleys, in empty rooms and quiet corners, the air tastes different. Thinner. Sharper. More honest.

That’s when I slip on “Air of December.”

Soft bass. Careful voice. Shadows tucked into the chords.

This song doesn’t promise warmth, and it sure as hell doesn’t ask you to smile.

It just says: pay attention.

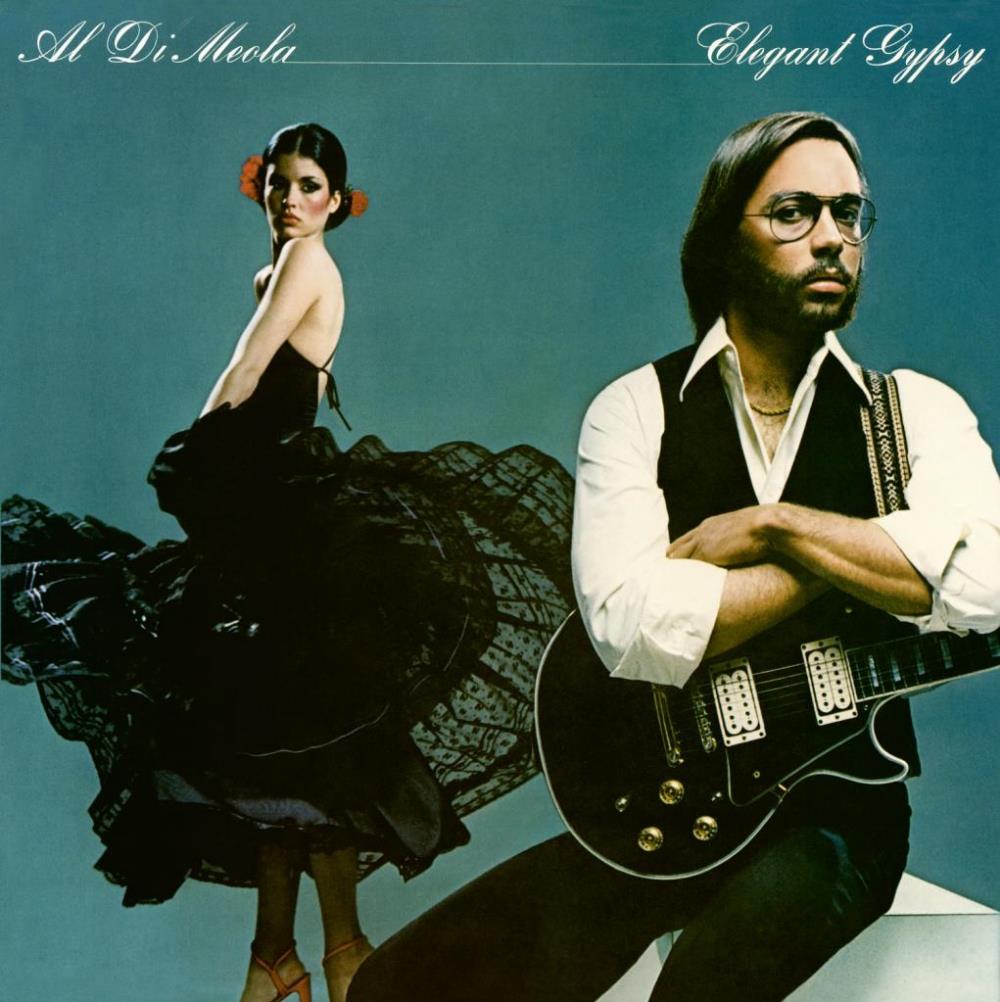

Edie Brickell & New Bohemians were never a mainstream machine. They had one catchy breakout moment, and most people froze them in that era like a photograph in a drawer. Air of December is one of those tracks even longtime fans forget exists. It’s not whispered in corners or held up as a hidden classic. But for the ones who hear it — really hear it — there’s a quiet respect. A recognition of its weight. Its weather. Its staying power.

The song opens like a door easing into colder air — a small shift in pressure you feel more than hear. The guitar stays clean but unsweet; the bass hums low like a steady engine under the floorboards; the drums hold back, giving the track room to breathe. The band understands restraint — they don’t fill the silence; they let the silence carry meaning. There’s distance in the mix as well, not loneliness but space, like the walls of the room are set a little farther apart than usual. It gives the whole track that “cold air in the next room” feeling — a quiet tension humming beneath the melody.

Brickell’s voice moves with deliberate softness.

She doesn’t chase the melody — she circles it.

As if she is dancing alongside it, doing her best not to disturb the melody, but to belong to it.

It’s intimate without being fragile or overbearing — confessional without wandering into theatrics. It respects the moment, and we appreciate that without even realizing we do.

This is the “close-but-not-too-close” mic technique: you feel near her, but not pulled into her chest. You’re listening in, not being performed to.

Her lyrics drift like breath on cold glass — shapes that form, fade, and return slightly altered.

Brickell doesn’t write scenes; she writes impressions.

Smudges.

Moments that land in your body long before your mind explains them.

That’s December — not revelations, just quiet truths catching you in the corner of your eye.

There’s also the emotional sleight of hand: a major-key framework phrased with minor-key honesty. Hopeful chords, weary inflections. Warm instrumentation, cool delivery. A contradiction — just like the month. This isn’t a heartbreak song or a holiday anthem. It’s a temperature. A walking pace. The sound of someone thinking as the sun drops at 4:30 PM.

Some songs become seasonal without meaning to — not because they mention snow or nostalgia, but because they inhabit the emotional weather perfectly.

This one does.

It sounds like a room after the noise has died down and the truth hasn’t found its words yet.

It sounds like someone sitting beside you, matching your breathing.

It sounds like December without the costume.

Most December songs want to wrap you in tinsel and memory.

This one just sits beside you.

Doesn’t judge.

Doesn’t push.

Just listens.

People claim they want authenticity in December — honesty, depth, meaning.

They don’t.

They want distraction wrapped in nostalgia.

They want songs about snow so they don’t have to face the winter inside themselves.

“Air of December” refuses that bargain.

It listens — and listening is dangerous this month.

Give someone a quiet December track and half of them will panic.

They’ll change it before the first truth lands.

Stillness has a way of turning the room into a mirror.

Most December listeners don’t want the real temperature.

They want the thermostat set to everything’s fine.

But winter doesn’t trade in lies.

And neither does this track.

Yet there’s a strange comfort in that kind of honesty.

The song doesn’t shield you from the cold — it invites you into it.

It says, look around, breathe, the truths you’ve been dodging all year are rising — and you’re strong enough now to meet them.

December strips everything down to bone and breath.

This track reminds you that what remains is still yours.