WHOT Episode 149 – “The Jungle Line” by Joni Mitchell

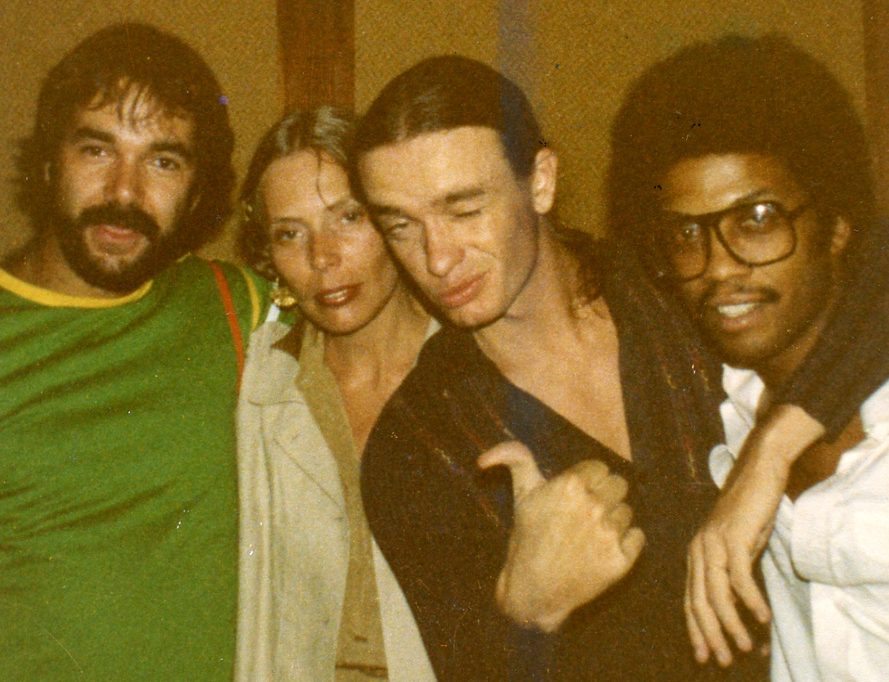

Hosted by Mangus Khan

[Drums begin—raw, repetitive, almost ritualistic. A strange synth cuts in like neon over ancient stone. Then: silence.]

“You’ve tuned in to Late Night Grooves.

WHOT.

The hottest in the cool.

I’m Mangus Khan.

And tonight—Episode 149—we don’t just press play.

We unravel.

Because some songs aren’t made to move you.

They’re made to unsettle you.

And if you’ve got the nerve to stay with them long enough…

They’ll show you parts of yourself you didn’t know were watching.

The track?

Joni Mitchell – ‘The Jungle Line.’

From The Hissing of Summer Lawns, 1975.

A record people didn’t understand then.

A record people are still trying to catch up to.

And this track?

This was Joni swinging a wrecking ball through every box the industry tried to trap her in.

She was folk, right?

Soft guitars. Laurel Canyon sunsets.

Not here.

This time, she leads with drums.

Field recordings of Burundi drummers pounding like a heartbeat through barbed wire.

Then comes the Moog synth. Cold. Detached. Watching from a distance.

And over that?

Joni’s voice.

Observing. Dissecting.

Cool on the surface. But listen closer.

She’s not distant. She’s wounded.

Because this song?

It’s not about jungle rhythms or abstract art.

It’s about the white gaze.

About how we turn other cultures into wallpaper.

“Rousseau walks on trumpet paths / Safaris to the heart of all that jazz…”

She’s talking about appropriation.

About aesthetic tourism.

About the quiet violence of being seen but never understood.

And while she’s at it?

She’s looking at herself, too.

Because Joni wasn’t afraid to hold the mirror up to her own complicity.

That’s what makes this track bold.

Not just that she named it—

But that she included herself in the naming.

This is self-interrogation in 4/4 time.

And it’s uncomfortable.

But that’s what evolution sounds like.

The Jungle Line isn’t smooth.

It’s jagged.

It’s intentionally unresolved.

The drums never let up.

There’s no chorus.

No payoff.

Just this loop—

Like a mind circling a question it can’t stop asking.

And if you’ve ever sat in that kind of silence—

You know what this song feels like.

It’s not just a sonic experiment.

It’s a reckoning.

Episode 149.

Joni Mitchell.

The Jungle Line.

A groove that doesn’t soothe.

A voice that doesn’t plead.

Just a truth that won’t be simplified.

This is Late Night Grooves.

WHOT.

And I’m Mangus Khan—

Still digging through the uncomfortable.

Still playing the songs that refuse to make you comfortable.

Still broadcasting for the ones brave enough to listen all the way through.”